The premise is simple. Set it and forget it. Vanguard and others offer this approach for target-date retirement funds. Of two investing extremes, there is an active self-directed retirement account, where you pick individual stocks and strive to have an edge (fewer than 1 in 200 with Vanguard accounts do this1), and there’s auto-pilot.

Target-date is auto-pilot squared. Target funds invest in index funds and adjust asset allocation from equity leaning, usually 90/10 equity-to-fixed income for those planning to retire in 30 years, down to 50/50 or less as retirement approaches.

Details behind this and other trends are covered in Vanguard’s report on “How America Saves.” It makes for a breezy skim or night read. This is just part of the defined contribution (DC) plans that cover 100M people and boast over $7.5T in assets. That’s enough to buy all the shares in the 17 largest publicly-traded companies in the US–from Microsoft to down to Pfizer.

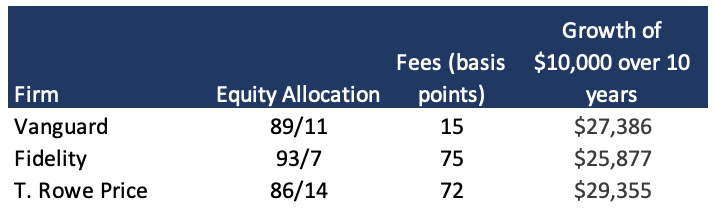

Target funds are cheap and huge. Vanguard charges a bargain of only 15 basis points or less (100 basis points = 1%, or $1.50 per $1,000 invested). Target investing is a growing trend and is expected to reach 8 of 10 Vanguard 401k participants by 2023, a 10x increase from 2007.

Individual investors aren’t as irrational as people think. The Vanguard report shows contributions from both employers and employees add up to 10% of salary, stable over the last 14 years. 9 of 10 account holders did no trading. “During 2018, only 8% of DC plan participants traded within their accounts, while 92% did not initiate any exchanges.” Younger employees are allocating more towards equities, in line with target-date approaches.

This is good news, but how does Vanguard compare to other investment firms’ target funds? I compared Vanguard’s 2045 index fund to those of T Rowe Price and Fidelity–there are now 223 such funds in this Morningstar category. Below shows a comparison with current equity allocations, fees charged, and the trailing 10-year growth of $10,000 invested in each fund, before fees. T. Rowe Price is doing slightly better, even if you added higher fees, while Fidelity is long on fees and short on returns. Higher fees on $10,000 over a decade could reduce investment growth by $800+. This comes with all the warnings and caveats of past performance not being a guide for the future.

Fees are a big deal and simple indexes are worth noting. To quote John Bogle in investing, “you get what you don’t pay for.” The 5x difference in fees that Fidelity and T. Rowe Price charge could pay for a lot of investor conferences in Miami–the Fidelity fee differences alone on $13B in assets for the fund, is $73M per year. This chart hides the humble S&P 500 index, which produced $7,500+ more than the target date funds. That’s 10 years of a rearview mirror bull market speaking, however.

Is there, or could there be a simple, low-fee product in healthcare with target-date auto-pilot attributes? All health insurance resets each year and is often picked with less consideration, and from a limited menu than our next washing machine purchase. Healthcare coverage changes with jobs, and nobody has an allegiance to the logo on their insurance card. Inertia is big too. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation study, only 1 in 10 seniors switch Medicare Advantage plans each year.

Health and wealth are at a natural intersection, and at a certain level of premature health deterioration (personal depreciation), health gets much more attention than wealth. In the key years of 50-70 there are many changes, screenings, and plan choices that most find hard to navigate. This could be an area ripe for more of a long-term, target-date approach. People need the right kind of simple, and with the consumers’ interests in mind.

The image is a word cloud I made from the first 10 pages of the Vanguard report.