Michael Burry, investor and mortgage crash money maker*, caused a stir in September when he called index funds a bubble, akin to subprime mortgages. Some High Priests of finance and fans of passive approaches lashed out on social media. Indexing is popular. Even Warren Buffett, a lifelong non-indexer, recommends index funds for 90% of his estate once he dies.

Burry’s unpopular view fits in the category of the Peter Thiel type question: “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?” Very few people came to Mr. Burry’s side of the tent. If it was a consensus it wouldn’t be fun.

He explained:

“…passive investing has removed price discovery from the equity markets. The simple theses and the models that get people into sectors, factors, indexes, or ETFs and mutual funds mimicking those strategies — these do not require the security-level analysis that is required for true price discovery.”

If there are fewer people calling strikes, especially in certain corners of markets, then there could be bad calls, too much groupthink, social loafing. If firm fundamentals lose importance and asset allocation is on auto-pilot, there are fewer people to call out management, vote against bad moves, or send letters to management bugging about healthcare expenses or corporate waste. Buffett says finance’s core goes back to Aesop’s story of a bird in the hand being worth two in the bush. When will I get the birds? Are the birds really there? What are interest rates like to discount those birds? Burry thinks too many people are ignoring bushes, interest rates, and if the birds have flown off.

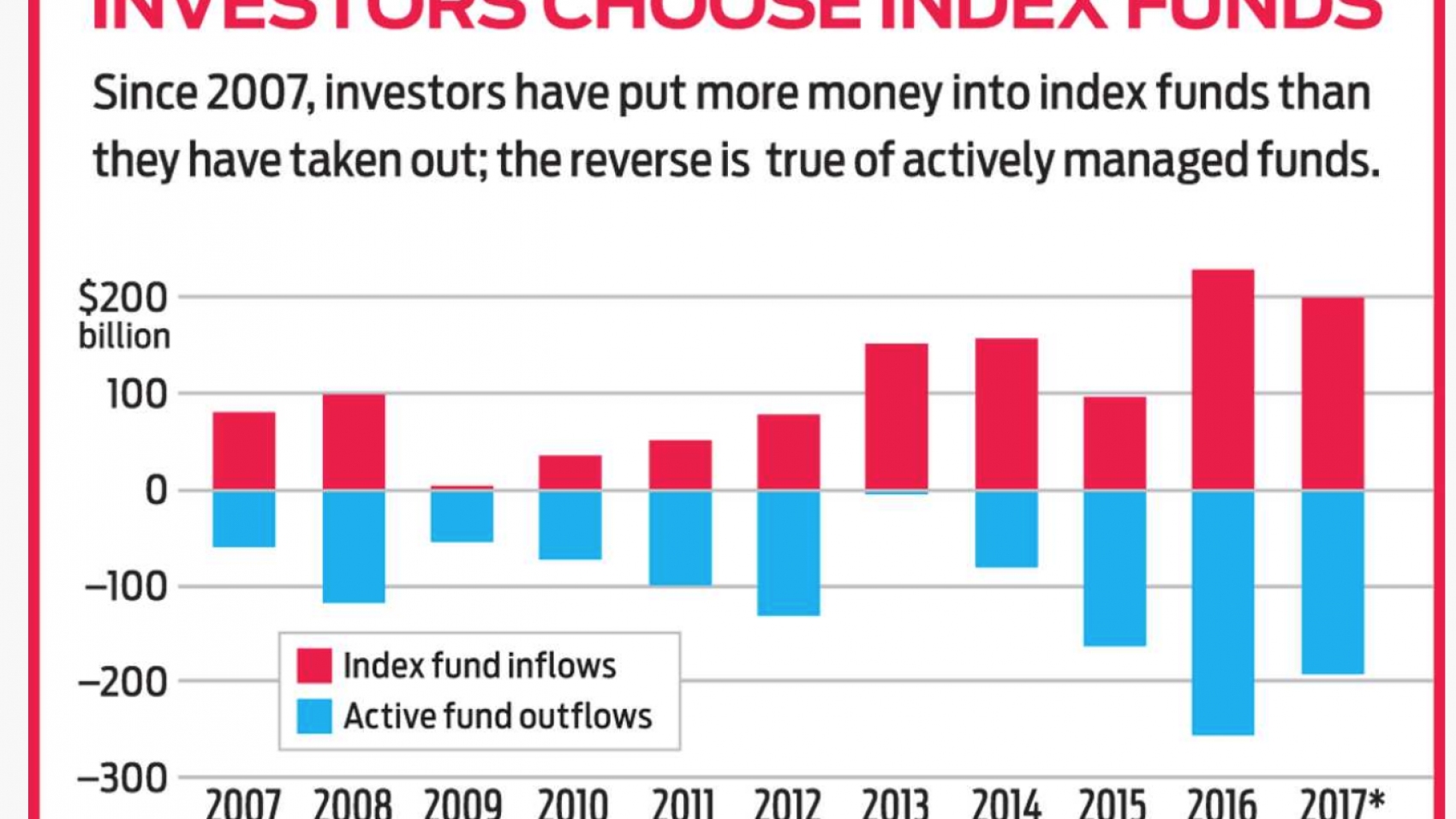

Detractors argue that there is enough price discovery, enough people trying to beat the market, and over 50% of assets are actively managed, searching for value. Like the national debt, it’ll matter at some point, just not now the thinking goes. Like debates about the fashionability of Crocs or the daily impeachment news, it’s best to keep a cool head. Anything the crowd follows should bring pause and reflection.

Bubble talk aside, with some forms of passive investing there could be high relative fees. A form of indexing, the target-date retirement fund, is one you set and forget for decades–passive on steroids. Every paycheck you buy the 2045 fund, which, if you’re planning on retiring in 2045, is about 90% stocks (think S&P 500) and 10% bonds. Fees are low: around 15 basis points (100 basis points = 1%) for Vanguard but could be 60-70 basis points with T Rowe Price or Fidelity. $500 more on each $100,000. It’s easy to say it’s small, but with 4-5x difference it starts to resemble the variation of getting an MRI at an imaging center vs. a hospital (hint: hospitals charge more).

Too much diversification can be bad. Indexing can lead to too much diversification: you don’t need to own fractions of 1-3k worldwide businesses and bonds from parts of tens of thousands of corporate issuers. Charlie Munger is not squeamish about concentration: “Warren (Buffett) always says that if you lived in a growing town and you owned stock in three of the best enterprises in the town, isn’t that diversified enough? The answer is of course it is… if they’re all wonderful places.” Some cite 15 companies in a portfolio as sufficient diversification. Many with an academic bent argue against this. Someone who runs an insurance industry or dental practice doesn’t worry about the concentration of risk in what is the engine of their retirement, their income. They care about their current skills and the value the market places on them.

While passive investing may not be a bubble, if more money and people move to it, more outsource the analytical work to others, Michael Burry could one day profit from another bubble’s pop.

*Christian Bale plays him in the movie The Big Short.