Over 30 million people in the United States start a new job every year*. We rely on past salary anchoring, asking around, the walls of internal company salary ranges, and sites like Glassdoor, to now know how much others are making in salaries and bonuses. But what about benefits? Often the biggest dollars outside salaries and bonuses are spent on healthcare: ~$10,000 per employee per year and highly valued by job seekers. A great piece appeared on HBR’s site about how important they are. As a note, while interesting and potentially big, for this analysis we’ll leave aside equity, unlimited vacation time, parental leave, ping pong tables, career growth, and others.

It’s hard to compare healthcare benefits because they vary so much, especially by industry and company size (think Google vs. Betty’s Diner), and because of information asymmetry. Asymmetry in general can be painful but insurance is priced to reflect it. One key example, adverse selection, says that since we know more about our own health, if we’re sick, we’ll tend to opt for richer healthcare coverage. Insurance actuaries are dull (insert your actuary joke of choice) but smart and compensate for this through prices. Adverse selection and its cousin moral hazard, are examples sometimes taught with the little guy hiding information, or having an informational edge, over the big guy.

But what about big guys having an edge over little guys? Companies know much more about how much benefits cost than employees. Employees get a job offer, often negotiate the pay package, and are presented a 30 page benefits guide full of smiling families riding bikes and playing with pets. Deep inside are 1-3 plans to choose from, along with a bimonthly employee contribution summary. As an epilogue, employees take the job and then see a five figure number in box 12 with code DD on their W2, the annual employer contributions. But that’s all too late.

What if you ask for $5,000+ more in salary to make up for benefit differences or company contributions to premiums? Twice in my career I’ve done this, and the last time it was $8,000. The best part was, I didn’t even have to show any evidence other than my statement from own pencil-to-paper math for family coverage: “I’d like $8,000 more to make up for the difference in benefit values and high employee contributions.” Fifteen minutes later it was granted.

The 2017 Kaiser Employer Health Benefits Survey is the preeminent survey on funding, benefits, costs, plan designs, trends, and strategies that companies have implemented or may implement in 3-5 years. Within the survey’s underlying data, the basis of the 200+ page report (something I have access to), are troves of interesting numbers hidden behind all the averages. I’ve used some of that data to write in the AJMC about the value of health insurance brokers and why we should rethink health risk assessments.

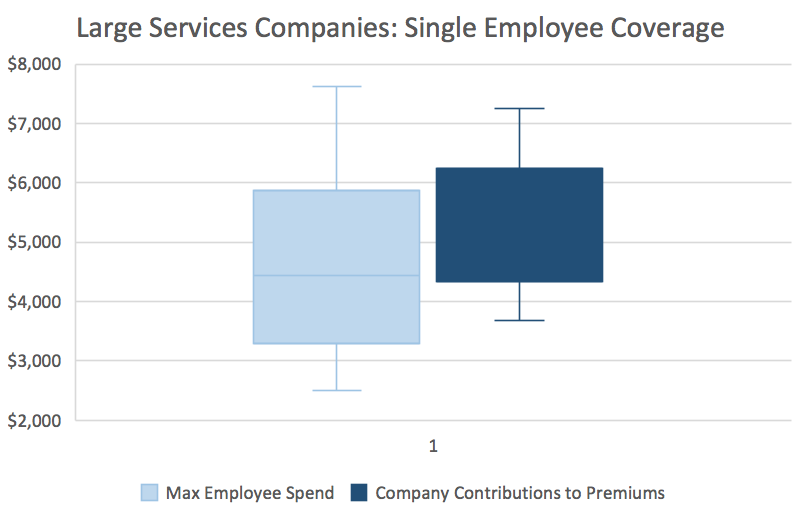

Using the survey data, there are two ways I like to think about benefits and their attractiveness. The below come from large service companies (n=387) for single employee coverage. The whisker plots reflect the range (10th-90th percentiles) and the boxes the interquartile range (75th to 25th percentiles). Stay with me.

- An employee’s maximum spend (employee premiums + maximum out-of-pocket). The variation between the 75th and 25th percentiles for large service companies is over $2,500.

- The other is the total dollar value of employer contributions to healthcare benefits. Here the variation in the box is $1,900.

Naturally, this comparison will vary wildly due to size, demographics, geographies, and health conditions of a work force, but controlling for these and sticking to size and industry is a great start.

Naturally, this comparison will vary wildly due to size, demographics, geographies, and health conditions of a work force, but controlling for these and sticking to size and industry is a great start.

With unemployment at record lows and lofty corporate profit margins, power is shifting to employees to negotiate higher salaries to make up for benefit differences. Of course, not all companies can be 90th percentile, but employees, with the right tools and info can have a little more sway in negotiations. It will also show a positive signal you’ve done research. More info across different industries and sizes is forthcoming, but adding light is a start to giving more power to the employees.

—

Note: *(325M Americans*63% workforce participation*62% ages 16-64)/average tenure of 4 years.