Volatility in investing can be a great thing. The attraction to Bernie Madoff’s scam can be better understood by its lack of volatility. His funds showed annual returns of an eerily consistent 10-12% and at one point reported 72 consecutive months of positive returns. His strategy used a split-strike or collar options strategy (not related to baseball or haberdashery), whereby you buy stock, sell a call option, and use the proceeds to buy a put option. It can work, but is not without risk and has down periods. It couldn’t have worked on the scale Madoff presented. Which is why it had to be a Ponzi scheme. Harry Markopolos saw through it after spending four hours doing the math. His 2005 17-page memo raised 30 red flags but was met with indifference.

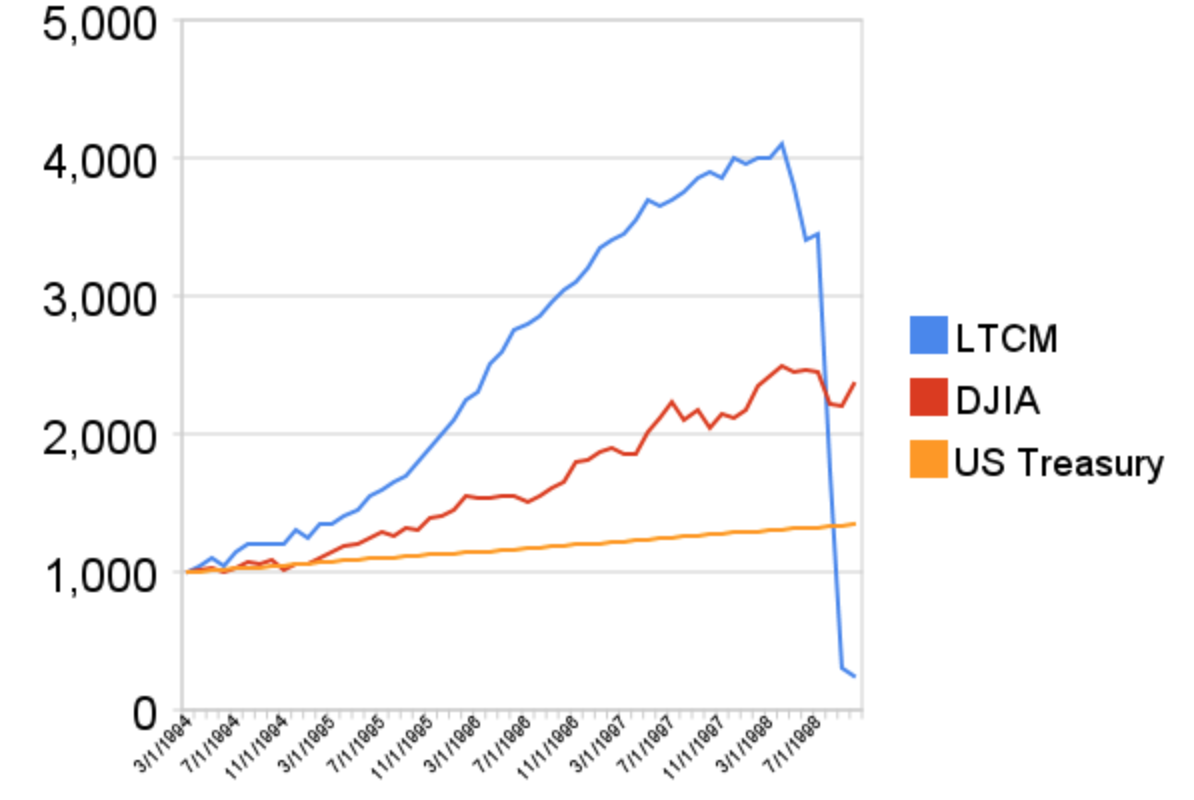

Long-Term Capital Management was not long-term even though it had two noble prize winners on its board. It blew up in the 1990s. The impetus was leverage on strategies such as convergence trading that was essentially picking up nickels in front of steamrollers by finding small market anomalies, amplified by debt. Absent hiccups, things were rosy. Then came the unforgiving Asian and Russian financial crises. The firm’s leverage went from the already high 25-to-1 (Goldman Sachs today has assets-to-equity of 14x) to 250-to-1. That closed the runway and the nickel collectors got crushed.

Stated numbers are always subject to hidden forces and risks, sometimes with disingenuous claims or partial truths. A fund that returns 15% when the market is up 3% needs at least a partial ‘how’ attached to it. If leverage, or debt in whatever form, is used 5-to-1 then the benchmark-beating return was related to leverage and should be adjusted. Process and an accounting of hidden risk matter when framing and adjusting outcomes.

Housing up to the mid-2000s did great as an asset class; it was also touted by economists as one that couldn’t go down. Loans, with government encouragement, were made with little regard to pricing risk. However, as with thermodynamics, where energy in a closed system can be neither created nor destroyed, investment risk cannot be destroyed. It can only be traunched, shuffled, or repackaged, and leverage and systemic failures can quicken it.

Finance usually describes risk as volatility and not in terms of the likelihood of total loss, which is the way Buffett and many others view it. In classic Buffett philosophy, he said: “It doesn’t make any difference to us whether the volatility of the stock market, you know, is — averages a half a percent a day or a quarter percent a day or 5 percent a day. In fact, we’d make a lot more money if volatility was higher, because it would create more mistakes in the market. So volatility is a huge plus to the real investor.” Not everyone is Buffett, but volatility is not all bad, even if finance professors equate it to risk. After all, over time cash and bonds are riskier than equities.

Healthcare carries risks. One is the inertia of autopilot. Employers, often the ones who control healthcare spending, stick with the same insurance company for 12-15 years (according to the 2018 Kaiser Survey). Trend of 2-3x inflation is just the “cost of business.” Costs in any given year can be volatile and subject to adjustments for plan design changes, demographics, implementation risks, and sometimes hidden contract risks. There is the risk of innumeracy that leads to too many programs, for example: intrusive wellness programs that employees loathe. You can save money and skimp on stop-loss insurance, the reinsurance firms use for high-cost claimants, only to have it bite you later. There are strategies that, without vetted contracts with providers, could lead to outlier risks on payments, balanced billing, employee satisfaction, and headaches (see many cases of reference-based pricing and the case of Glenn Dennis vs. Memorial Hospital of Martinsville & Henry County).

Volatility can be a benefit with the right temperament and willingness to learn. Not being afraid to look stupid by asking questions is one of life’s great dividends. Lack of exposure to variability is one reason people talk about the need to go camping or play monopoly with their partner prior to marriage. You need to see some tense moments to flush out the truth. Just be careful of hidden risks. They’re not always disclosed in fancy reports.

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash